What is a law of demand?

When the price of something falls people usually demand more of it. This happens because you can now afford to buy more of it and also more people can afford it now. This is called the law of demand.

This means the higher the price, the lower the demand is, and the lower the price, the higher the demand for any normal good or service. Undeniably, a change in people’s tastes, income, and preferences can affect the demand for something, but we will assume that these other factors don’t change, so we can only focus on the relationship between price and quantity demanded.

The Law of demand is a key economic concept and has many uses and implications in our daily lives. The demand curve slopes downward when you plot the price on y-axis and the quantity demanded on the x-axis.

But does it happen to every single item and is there a way to find out by how much?

The answer to this is yes, and this brings us to another important topic, which is the price elasticity of demand.

By how much does the demand change with a change in its price?

The answer to this question depends on how responsive or sensitive the demand is to a change in price.

Economists call it elasticity of demand. Similar to the concept of a stretch of an elastic, we can look at how much does the demand stretches (changes) in response to a change in the price.

Many factors affect the elasticity of demand. Whether there are any substitutes for that good, if the good is a necessity or not, loyalty to a specific brand of good, time duration, and how much income you spend on that good all play a role in determining its elasticity.

In economics, if the percent change in the quantity demanded is more than the percent change in the price, we call it elastic. Going with the same logic, if the percent change in the quantity demanded is less than the percent change in the price, we call it inelastic.

Just if you are interested, here’s the formula to calculate elasticity.

So if the value is greater than 1, it means the good is elastic and is sensitive to price change.

So, those goods where a small change in price creates a big change in the quantity people demand, we call them having an elastic demand.

Similarly, those goods and services, where a change in price do not cause a change in demand, have inelastic demand.

Who uses this calculation anyway?

Businesses and corporations use this calculation to see whether their total revenue will increase or decrease, due to a decrease or increase in price. This also helps them in deciding how much discount to give you during the holiday season.

The government also uses price elasticity to select goods and services on which to impose excise duty for maximum revenue.

If you are interested in knowing more uses, here is another article that lists some other ones.

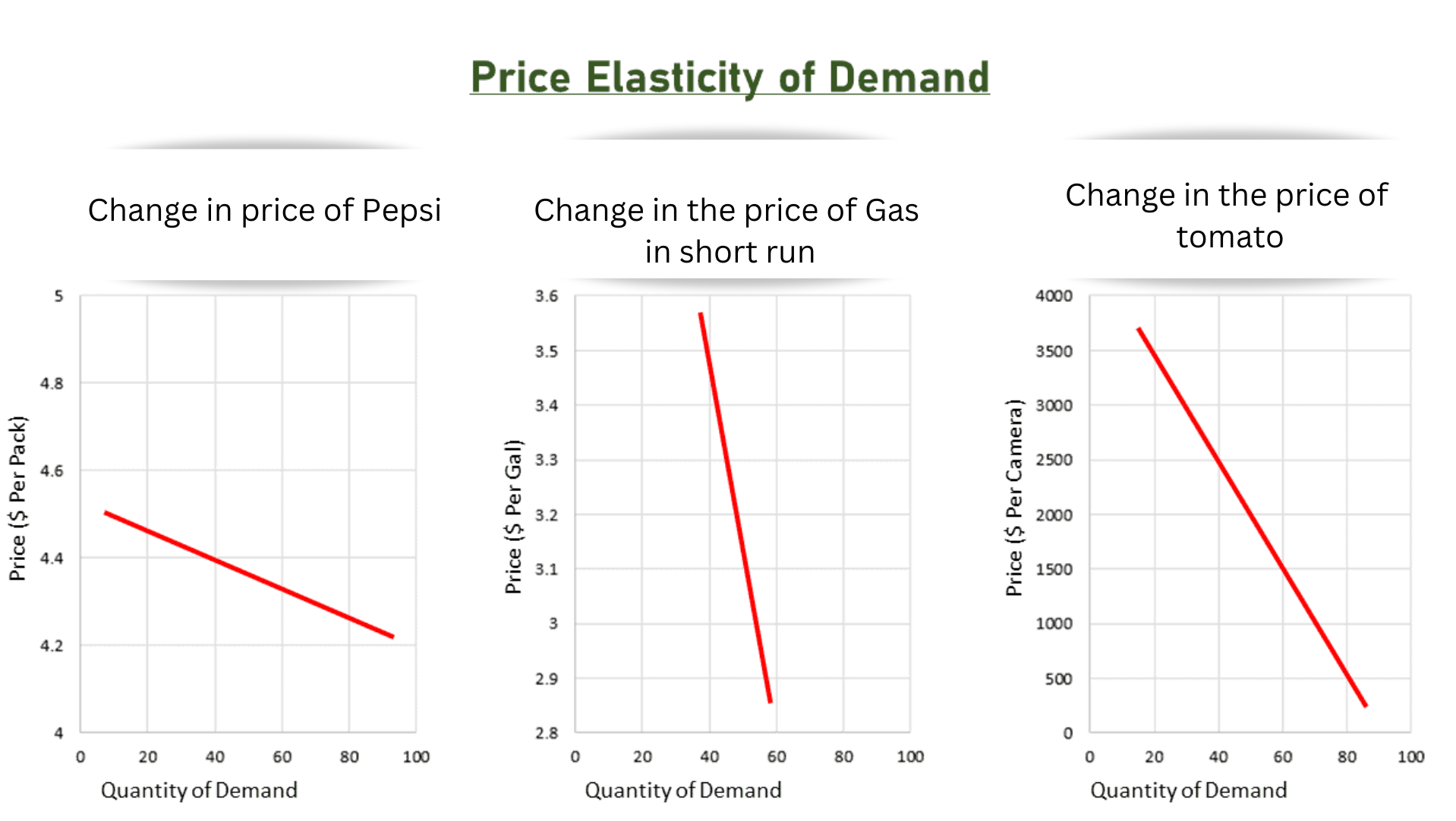

Let’s look at some real-life goods and services to understand this concept better.

Inelastic goods

A classic example of inelastic demand is gasoline in the short run. Anyone going to work every day needs gasoline to drive. Even if there is a rise in the price of gasoline, people will still need it. Some of us might find a carpool or use public transport, but for most of us, we will still need to fill up our gas tanks despite the high price.

Addictive things like tobacco have inelastic demand as well. Smokers still use it even if there is rise in its price. Similarly, certain prescription drugs, like insulin, because of their limited substitute availability also have inelastic demand.

Elastic goods

Now, let’s look at some things which have elastic demand. If the price of Pepsi goes up, a lot of people can switch to a close substitute like Coke, unless they are die-hard Pepsi fans. So Pepsi has a very elastic demand. So any item that has a perfect substitute, will have an elastic demand.

The duration of a price change and the category of the good or service also makes it more elastic. Too complicated! Let me example this with an example.

In my example above, over the short run, people may not find alternatives to going to work if the gas price goes up, so the demand is inelastic in the short run. However, over the long run, people can find alternative options, like using electric cars or working from home. Thus, the demand for gas will be elastic in long run.

A specific brand of milk can have elastic demand if people can substitute it with other brands, but milk in general will have more inelastic demand, as there are not many substitutes for dairy lovers. So here you saw the broad category of food has inelastic demand, meaning its demand won’t change if the price of milk goes up. However, a specific brand of milk can see a decrease in demand if its price increases.

Are there other types of elasticities as well?

Yes, there are two other types – cross elasticity, which looks at the effect of a change in the price of a substitute or complementary good or service), and income elasticity (which looks at the effect of change in income on quantity demanded. These are important because changes in demand can also happen due to changes in income level and price of other supplements or complementary goods.

But to not make the post overly long, I only focused on price elasticity in today’s post, as we wanted to see the effect of a change in price only.

Hope you found this microeconomics post helpful, to see my other microeconomics posts, please click here. And, yes, if you can think of another elastic or inelastic good or service, please write in the comment below.